What is this? 🔗

Imfs is a reactive, immediate-mode functional abstration over Minetest's often cumbersome string-based formspec format. What this means is that:

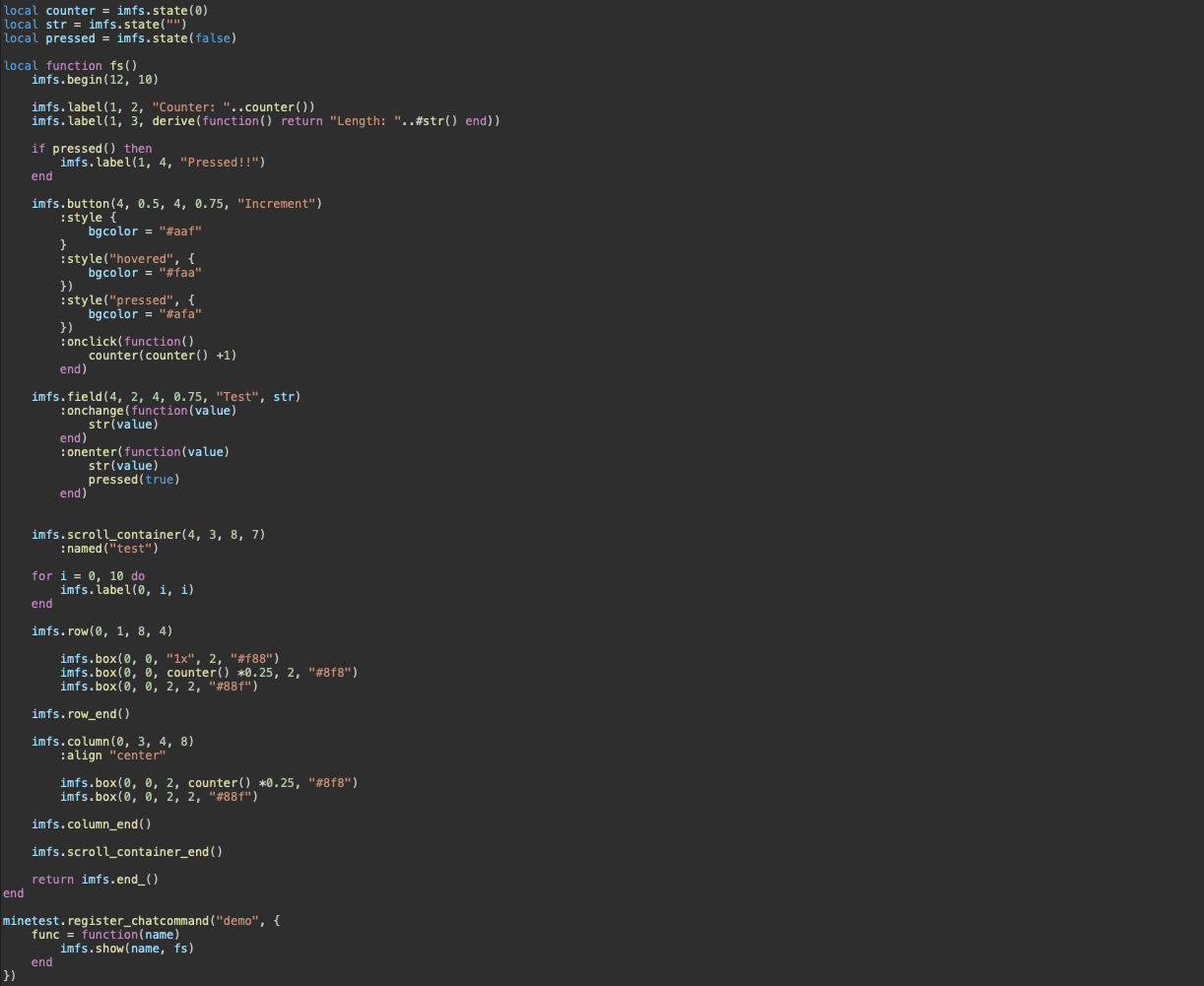

- An interface (or "formspec") is represented by a builder function, which creates and returns an imfs element tree.

- Every time state changes, the builder function is called again to create a new tree reflecting the new state.

- Elements and containers are represented as linear function calls. You don't have to care about child management or tree manipulation; imfs does that internally.

- You don't have to manually interpolate variables.

- You don't have to remember to update the UI every time you make a state change. By wrapping data in states, you can make a fully reactive UI contained almost entirely in one builder function.

- You don't have to care about element names and event handling. With imfs, event handlers can be registered inline, while the library does the rest.

- You don't have to care (as much) about manually doing layout calculations. Imfs provides percentage units and flex containers to do relative and automatic layouting.

Due to ContentDB description length limits, refer to the README for example code and API reference.

Concepts 🔗

Builder functions 🔗

A builder function is a function that creates and returns an element tree to be rendered. There is thus only one requirement of such a function: it must call imfs.begin(window_width, window_height), then return imfs.end_(). Elements may then be added between the calls to start and end_. The most important advantage of this approach is that it allows you to perform conditional rendering merely by using if statements, in addition to any other operations you may see fit.

Builder functions are used by either imfs.show (to show an interface to a player) or imfs.set_inventory (to set the player's inventory). These functions are described in more detail below.

You can pass a table as the last argument to an entry point like imfs.show to hold state external to the builder function; it will then be passed as an argument to the builder function during every rebuild. This way, you can declare the builder function itself in one place and use it in another without having to rely entirely on closure capture or global variables.

Imfs does not strictly require using a builder function: if an interface is purely static and need never change, you can use a prebuilt element tree instead of a builder function, which avoids rebuilding the tree every time the interface is shown.

Elements 🔗

Elements are created with function calls, like imfs.box(0, 0, 2, 2, "#faa"). This creates an element, adds it to the current container, and returns it. For simple elements like label, this is all that needs to happen; however, some elements, like field, support further configuring the element using chainable methods, like so:

imfs.field(4, 2, 4, 0.75, "Test", str)

:multiline()

:onchange(function(value)

print(value)

end)

Notice that you can register an event handler with :onchange; in this case, the event handler will be called whenever a change in the field's value is detected. This makes event handling quite straightforward, since event responses are tied directly to the element that is expected to trigger them (rather than being crammed together in a single callback registration somewhere else).

Because elements are just function calls, you can easily create your own widgets simply by creating a function that creates a predefined sequence of elements. For example:

-- Adds four colored boxes using a single call.

local function quadbox(x, y, w, h)

imfs.box(x, y, w/2, h/2, "#faa")

imfs.box(x + w/2, y, w/2, h/2, "#afa")

imfs.box(x, y + h/2, w/2, h/2, "#aaf")

imfs.box(x + w/2, y + h/2, w/2, h/2, "#ffa")

end

local function builder()

imfs.begin(12, 10)

imfs.label(0.5, 0.5, "Quadbox:")

quadbox(0.5, 1, 4, 4)

return imfs.end_()

end

More advanced widgets with chainable methods can be created using Lua classes (the implementations of the builtin elements typify this technique).

Containers 🔗

Containers are, in essence, lists of elements. There are three types of containers: scroll containers, layouting managers, and the formspec itself. The top-level formspec container performs minimal layouting; it only evaluates percentage units to always be relative to its own size. The scroll container functions similarly, but wraps its children in a scroll_container[] element internally.

Besides these basic containers, however, imfs also provides several layouting containers. These are:

imfs.group: The same type of container as the root; the positions and percentage units of its children are relative to the position and size of the container respectively.imfs.row: A flex row. This automatically positions elements within it based on the provided gap and alignment. Child elements may specify their width as a grow ratio like"1x"to dynamically resize to fill any empty space in the row. Higher grow ratios will cause the element to take up a larger portion of the available space compared to other dynamically sized elements.imfs.column: The same asimfs.row, but in the vertical direction.

To create a custom layouting container, the procedure is essentially as follows:

- Create a Lua class for the container.

- In the class constructor, call

imfs.container_start(container)with the newly created container instance. - Create an end function that wraps

imfs.container_end(). - In the class's

render(self)method,for _, child in ipairs(self) do child:render() end. - Add custom layouting calculations to

render(), and pass modifications tochild:render().

(Be advised that certain elements, like labels, have no knowable size.)

State 🔗

Being able to imperatively create a UI is nice, and already better than formspecs, but many UIs must dynamically update to reflect state. Doing this manually can become bothersome, which is why imfs is also reactive. This means that it can trigger a rebuild automatically whenever state changes, saving you the trouble of remembering to update the UI when you update a variable. To do this, you must set any of an element's properties to a state object.

State is created by wrapping the initial value in an imfs.state, like so: local counter = imfs.state(0). To read the state's value (and register it as a dependency of any active observers, like an imfs UI), call it like a function: counter(). To set the state's value (and notify any dependents), call it with the new value: counter(3).

Imfs also provides imfs.derive, which creates a derived state from a function based on the states accessed in the funtion. This way, you can perform operations on a state's value for display while still depending on the state from the element involved. It should be noted, however, that beause full rebuilds for every change are an intrinsic property of formspecs, there is not currently much benefit to having a certain element depend on a state rather than the formspec itself, so in most situations derived states will not really be useful. An exception is if you want to create side effects; since imfs.derive takes a function, you can do anything you like in that function, so it might sometimes be useful to have a function that is called whenever a dependent state's value is changed. (Indeed, this mechanism may prove more useful in non-UI applications than in actual imfs UI.)

Each state object includes an _old_val property, which holds the value the state had before it was last changed. In addition, you can also use the _val property to access a state's value directly and bypass dependency resolution.

If you want to use the state API for a system of your own, remember that:

- State objects store dependents in

_getters. - When set, a state notifies each entry in

_gettersby calling that object's:update()method. - To collect state dependencies from a given function, 1) create a tracking table and

table.insert(imfs.state.observers, tracker), 2) call the function, and 3)table.remove(imfs.state.observers). The tracking table will then be filled with all states that were accessed between thetable.insertandtable.remove.

Due to ContentDB description length limits, this description continues in the README with example code and API reference.